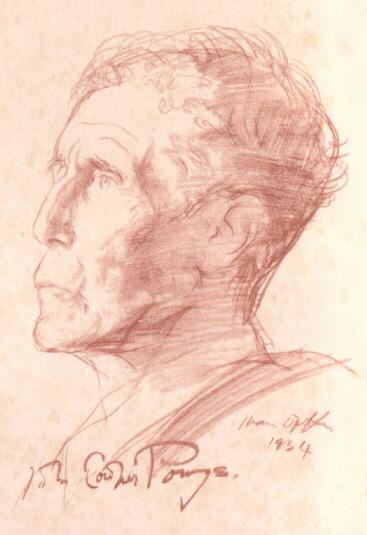

The Wayward Isles | Site Index | John Cowper Powys | Home | Memoirs | Letters & Journals | Miscellaneous Pieces

How many autobiographies have ever been written in which the author fails to mention his own mother? One at least: and in this instance he goes further and omits from his narrative any reference to his five sisters and two wives. If I add that his novels which were already renowned and remain as 20th-century classics are scarcely mentioned either, you may wonder what, in 650 pages written at the age of sixty, the author considered worthy of inclusion. All public revelations at bottom are games in which concealment plays a major part: the more one lays oneself bare, the more one keeps hidden. Like the Confessions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the Autobiography of John Cowper Powys contains the kind of intimate confessions that one would be reluctant to reveal to one’s best friend:

To fall at the feet of an imperious mistress, obey her mandates, or implore pardon, were for me the most exquisite enjoyments . . . It will be readily conceived that this mode of making love is not attended with a rapid progress or imminent danger to the virtue of its object; yet, though I have few favours to boast of, I have not been excluded from enjoyment, however imaginary . . . I have made the first, most difficult step, in the obscure and painful maze of my Confessions. We never feel so great a degree of repugnance in divulging what is really criminal, as what is merely ridiculous.

[This quote comes 4887 words from the beginning of the Confessions, Project Gutenberg version]

The above quote is from Rousseau!—but Powys in like manner tries to express and thereby understand his powerful erotic impulses, tracing this aspect of his being from earliest memories through to maturity. A strength of Powys as a writer is to work out (perhaps exorcise) his innermost feelings in an intimate sharing with the reader. His Autobiography has the spontaneity of a letter to a friend, with the dithyrambic passion of one of his lectures delivered in the States to audiences hungry for culture.

His mother is acknowledged in a simple dedication "to Mary Cowper Powys", though by the time of publication she had long passed on. As to why he does not mention any of his most enduring relationships with women, we may put it down to chivalry. But another kind of relationship is dwelt upon, at great length: woman as an imaginary being or as an impersonal object of desire.

He was subject to powerful, irrational impulses, including sadism, though his sensitive conscience and abhorrence of actual cruelty made him the kindest of men, and he took enormous care not to stimulate any kind of prurience in his readers. To make sense of the irrational and not suppress what provided him with inspiration, he would often ascribe it to extra-terrestrial or cosmic forces which have the power of interacting with Nature and humankind. A born outsider, he can imagine himself as having come from Saturn, a planet classically associated with a Golden Age of innocence:

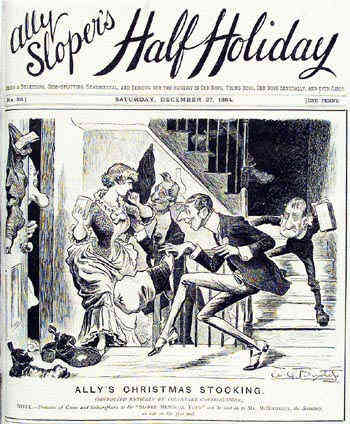

For the truth is, what I was so intensely attracted to, what I worshipped in those days to a point of idolatrous aberration, are hardly of the feminine sex at all! It is as if I had been born from another planet—certainly not Venus: Saturn possibly!—where there was a different sex altogether from the masculine and feminine that we know. It is of this sex, this Saturnian sex, that I must think when in the secret chambers of my heart I utter the syllable "girl". . . . The maternal instinct in women, so realistic, so formidable, so wise, so indulgent, is more remote from, and destructive of, the sylph-nature—the nature of these girls who are more girlish than girls—than the spirit of Hercules himself.[Page 206]

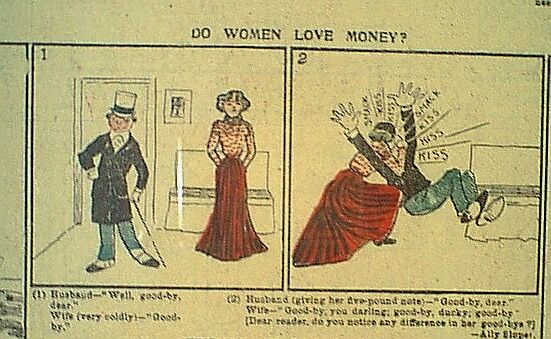

"These Ally Sloper young ladies I would cut out with trembling hands and carry about with me in my pocket. Is it not strange how moralists forget their own early feelings in such matters, how entrancing, and also how harmless, they were!"

And when he speaks here of the maternal instinct his own mother, who has given so much of her own life in child-bearing and nurturing, must be the prime example in his thoughts. Perhaps he sees how much she has sacrificed of her own spiritual and creative life, for the sake of motherhood; and so his reaction is to be repelled by the overtly reproductive aspects of femininity.

In the custom of his time and class, Powys was educated in all-male enclaves, including his public school Sherborne and his Cambridge college Corpus Christi, but makes it clear that his attitudes—not just to women—arose in spite of these environments, not because of them. Dropped mysteriously from some other planet into a succession of populous hearths, he forges his own path, guided by "a desire to enjoy the Cosmos, a desire to appease my Conscience, a desire to play the part of a Magician, a desire to play the part of a Helper, and finally a desire to satisfy my Viciousness" [Page 7]. He calls himself "neurotic", or "never entirely sane" [Page 593].

His wariness of the reproductive feminine mammal is confessed when he speaks of his dog Thora:

I had occasion ere long, as may be believed, to realize that the companion of my walks belonged to the feminine sex, that fatal sex with whose existence, when I tried under the influence of Plato to obliterate it, the sun and moon had gone out, and the realization that until this dog’s death all my walks upon the surface of the grain-bearing earth were to be, so to speak, "feminized" caused me an epoch of extraordinary suffering! A gulf of femininity opened beneath my feet. . . . I became panic-stricken lest I myself should develop feminine breasts, breasts with nipples, resembling the dugs of Thora. [Page 222]

Carefully omitting any reference to his wife as a person, even as a mother to his son, he offers himself to be pilloried by the conventionally-minded:

The question arises would a love affair have saved me at that epoch? Hardly! I was at that very time on the point of being happily married, and this maniacal pursuit of the sensations of impersonal lust increased rather than diminished after my marriage. [Page 217]

The word "mother" occurs only twice in the entire book [e.g. Page 583], both times in reference to the influence women had on their men to persuade them to enlist in the World War. An alert reader may trace the few occasions when coded references to a sister may possibly occur. When he goes on a protracted tour of Europe, "along with the best possible of companions", there is no doubt, from the censorship of further detail, that he’s referring to a woman of the respectable kind, perhaps a sister or wife. When he hires a "shanty" with someone in upstate New York—this is before his move to Phudd Bottom—he refers to "my blood-crony & I" [Page 595]: surely to avoid the taboo word "sister".

He doesn’t have any problems about describing his encounters with the kind of women whose favours can be bought, whether with money, gifts of clothes, or in the case of "Tom’s girls", with recitations of poetry. He devotes a few pages to "a very spirited and beautiful girl" who insisted on dressing as a boy whilst accompanying him and his friends in Venice. But these adventures are by no means straightforward erotic encounters: his reticence and circumlocution seldom clear up the question of "did he or didn’t he" achieve normal physical consummation with them. He’s attracted in the first place because they appear to be examples of the Saturnian girls that turn him on so much. But he discovers in their "shabby bedrooms" that they are just like himself, kindly and in their own way fastidious. So his lust dissolves into something which in his eyes destroys it: a romantic tenderness.

In describing the varieties of sexual attraction Powys can be an extraordinarily subtle analyst. In his novels, especially Maiden Castle and Owen Glendower which followed the Autobiography, the respective heroes No-Man and Rhisiart are each simultaneously attracted to several women. He is brilliant at distinguishing the feelings of the two lovers in a relationship, showing empathy with all his characters and special insight, so far as I can see, into the feminine psyche. But in his non-fiction masterpiece he reveals no secrets of real-life loves. Unlike the ignoble "kiss-and-tell" writers of today, he betrays no woman in his memoirs, whether lover or relative. This leaves him free to confess how he would gaze at the legs of girls on Brighton beach with that "impersonal lust"; or visit burlesque shows in the States, much as he hated the humour of their stand-up comedians, for a glimpse of their chorus-girls; or even haunt the peep-shows in coin-operated galleries. It became an obsessive fetish to pursue his desire, not for a real, whole woman, but "particular aspects of the feminine shape" which aroused his "intense religious idolatry".

"My own feelings, I know, were touched with a kind of quivering poetry of lust, that was at the extreme opposite pole from all indecency."

On the other hand, the encounters which he recalls with greatest fondness are with the Liverpool girls, from offices and factories, that he met through his friendship with Tom Jones. Though he is always reticent about any physical details, he hints that the girls got pleasure from his reading poetry to them and he got pleasure from having them on his lap and caressing them.

I have had love affairs at other epochs. I have had romantic infatuations at other epochs. These Liverpool experiences were neither love affairs nor infatuations. They were, purely and simply, friendly erotic encounters between men and women. They were enjoyed with no afterthoughts of emotional agitation, no complicated responsibilities, no tragic jealousies. They were experiences of perfectly simple, honourable, delicious pleasure on both sides. They were Arcadias of idyllic felicity. [Page 364]

In the entire book, he denigrates no-one but anonymous "society hostesses". He writes warmly of many male companions, especially his father and brothers. I could believe he wrote it expressly in an attempt to explain himself to his brothers, whose opinion matters more to him than any worldly fame. Though beautifully written—there’s not a boring page, for he knows how to captivate the reader—it’s certainly not an attempt at self-publicity. The very qualities which would have made it a best-seller—scandal, gossip, malice and prurience—are entirely absent, and even his most memorable characters—"the Catholic", Tom Jones and of course the constant presence of his father—are sketched in very lightly. If I had read only his Autobiography, I wouldn’t have thought him capable of writing all the love stories—so varied, tender and memorable!—which fill his novels.

Though his early domestic life with mother and sisters is completely missing from the Autobiography, it seems to be evoked in his last piece of fiction, the whimsical All or Nothing. The twins John o’ Dreams and Jilly Tewky, with their mother and father and grandfather and aunt, all live in a house called Morty where their life is centred on a great mahogany dining-table, reminiscent of the vicarage of his Montacute childhood. The twins are very close. They fall in love with another brother and sister, Ring and Ting, the children of a giant who is slain by John o’ Dreams. Amongst many fantastic adventures, God incarnates as a cockroach and the twins’ father, Nezzar Nu, is erotically attracted to a fallen star Lalanika—who explodes in a white flame before he can yield to any temptation. And towards the end Nezzar Nu discusses the forthcoming weddings:

". . . you must realise that from what we both have seen, John and Jilly are both very much in love with each other. People call it incest when brothers and sisters treat each other as lovers, but from what I’ve seen, and not only in their case, it is dangerous for anyone, whether parent or relation or outsider, to speak of this, because the division between the feeling of lovers and the feeling of brother and sister, especially in a case like this when they are twins, is a thing so delicate and subtle, and a thing so criss-crossed with emotional complications that it requires extremely cautious and careful handling". [All or Nothing, Page 200]

This provides another angle on why certain significant personages have been omitted from the Autobiography. This joyful account of adolescence, idealized, fictionalized and written in his late eighties, still has something to reveal about his feelings and formative experiences.

What is the enduring significance of this Autobiography, other than the masterly style? In courageously accepting himself, the author inspires the reader to do likewise.

"And why," I asked myself, "should I not be what I was born to be in my deep heart?"

Was it not the whole secret of personal life to find out what your innate nervous and mental fatality was, and then to drag it into your sorcerer’s cell and work magic on it . . . ? [Page 465]

I’ve often wondered if John Cowper Powys is so little known because he and his admirers are the "odd ones out", and if the majority who don’t seem to care for his work have nothing in their experience to relate to it. But I don’t think it’s that! He explores a layer of being which may be different in all of us, but in itself is universal and for each to discover.

© Ian Mulder 2002

For more on John Cowper Powys, see www.powys-lannion.net The Autobiography is long out of print. Here's a link to Alibris where you might find a second-hand copy:The Wayward Isles | Site Index | John Cowper Powys | Home | Memoirs | Letters & Journals | Miscellaneous Pieces